Happy Birthday Tijuana

"Poor Mexico: So far from God and so close to the United States of America."

- Porfirio Díaz, President of Mexico

(November 29, 1876 – December 6, 1876; February 17, 1877 – November 30, 1880; December 1, 1884 – May 25, 1911)

For one hundred and nineteen years, Tijuana has officially been a city, in Baja California, surviving a revolution, a hostile takeover, various floods and fires, tourism, Hollywood, gangsters of various nationalities, crooked politicians and crooked police officers, and various gringos like me and Daniel and Darren and Jeff. Tijuana survives in spite of the big metal fence, the department of homeland security, the ever-increasing influx of Chinese immigrants, dust, and a peso weakened by its relationship with the dollar. Tijuana is doing just fine, she still sparkles respectably in spite of her reputation, people here are still making art and giving the world a big crooked smile like a big-nosed clown at the circus.

Happy birthday, Tijuana. Happy birthday to you.

I am celebrating by drinking Tecate beer, out of the handy one-point-two liter bottle. Anna is going to bake a cake, and make the frosting from scratch, using sour cream and cream cheese. She loves to bake. I imagine that there are activities all over the city, or at least there should be. Someone should throw a parade, school children should be proudly marching down some blocked-off street somewhere. But I have the feeling that this day will go largely unnoticed. This fits, because Baja California went largely unnoticed when Tijuana was born. Porfirio Díaz had more important matters to attend to, I reckon.

In underdeveloped nations, one comes to expect that things aren’t always so smooth. When looking around, the inevitable conclusion is reached that there isn’t going to ever be enough money to fix everything. One accepts it; otherwise one would go insane. Maybe I am insane. That would explain a lot. That would excuse me from all of this, perhaps I should just drink a lot of tequila and call it a night.

One issue that anyone has no choice but to shake hands with in Mexico, is the unarguable fact that it does not at all run like the United States of America. However, it is easy to point out the similarities; a constitution, a federal republic, a democracy, a distinct flavor of freedom, three independent branches of government, and so on. The constitution of Mexico guarantees citizen’s rights, and each of Mexico’s thirty-one states also has its own constitution, even the Federal District. The United States of America is basically set up the same way, long before Mexico might have used that blueprint to build its own political machine.

These similarities are interesting in respect to the stark contrast of the colonization of the two countries.

Expansionist England’s idea of colonization was vastly different from the approach that Spain used in pillaging gold, silver, and other riches and resources from newly discovered lands. The North American indigenous tribes were scattered, unsophisticated, and easily disposed of for the most part. Ultimately, these tribes were driven into quarantine and permitted to exist in certain patches of land under terms that changed according to the needs of the settlers. It was relatively easy for the most part, because there were so few of them to deal with. Some assimilation occurred, mostly through marriage, but to a larger extent this practice of quarantine continues today, arguably, except that new gambling institutions have granted some of these small tribes an opportunity for some small form of economic autonomy.

Good for them.

In contrast to England’s role in the Americas, Spain sent conquerors in order to establish their presence. The Aztec and Inca Empires numbered twenty million each, and both were already established, complex, and thriving civilizations. After conquering these civilizations, the Spanish then assimilated their peoples rather than to drive them out or pen them up. This was accomplished through religious conversion, coercion with enemy tribes, and the accidental introduction of smallpox - the latter of which killed up to fifty percent of the Incas and up to ninety percent of the Aztecs. For the Aztecs - and then the remaining Mayans two centuries later - the pure indigenous, the mixed, and the land owning Spaniards formed a society, and then re-formed it again, and yet again.

Modern Mexico was born from this assimilation.

Cooking has become a passion for me these days, cooking and writing, but cooking especially. My challenge has been to do more with less, and it’s surprising what happens when I stop and think about what substitutions I can make and how I can arrange things. I have no actual grill, yet I can grill inexpensive fish in butter and spices that no restaurant here could ever match. I made macaroni with cheese from scratch last night that could be served at a gourmet banquet, but I have no cheddar cheese. I also learned that cream cheese doesn’t melt well in a microwave oven, that only a double-boiler and a lot of patience will do the trick. Not having a double-boiler, I make them, I use everything from baling wire to spare cooking utensils. I am fucking MacGyver in the kitchen.

Neither the cooking nor the writing is making me any money.

So, I have plenty of time to think, and the funniest thought occurred to me recently, it is one of the few times I’ve actually laughed in recent weeks. I said it out loud. I said to the computer, over the constant hum that accompanies the radio. I said it to the half-full super-caguama of Tecate and the ashtray full of cigarette butts. I said it to the only person listening.

"This depression is really depressing," I told myself.

Something will break soon, it always has, even here. I reckon I could work as a Mexican in some capacity if I wanted to straighten out my paperwork, but a forty-eight hour workweek would defeat the purpose of getting any job that would afford me the time to write more. There are opportunities in the United States that pop up, but I would rather stack boxes on a conveyor belt than to be some unappreciated cog in someone else’s machine – I’m sick of beating my head against a wall. If I’m going to work at anything other than writing, then I need a job that won’t make me insane; or even better, I need to figure out how to market my writing skills. Marketing myself has always been my greatest weakness.

In the meanwhile, I am cooking dinner, as inexpensively as possible. Tonight, we are having sopes, Mexican soul food. Since I already have Maseca, and cooking oil, and an onion and some garlic and salt and water. For five dollars and fifty cents, I just procured dry crumbly cheese (queso cotija), serrano chiles, tomatillos, and two packages of chorizo. This will feed six people until they are full and happy and I will still have plenty of sopes left for lunches tomorrow.

The tomatillo is an amazing fruit and an essential ingredient in most green salsas in Mexico. The flower blossoms and then a husk forms and the fruit grows inside of it. The surface of the fruit underneath the husk is sticky, and it isn’t uncommon to find dead insects that have unwittingly found their way into the husks prior to harvest. Then trapped onto the gummy coating of the fruit; unable to move and unable to consume anything, they are stuck and then die. Sometimes I feel like one of those insects, and the world is a tomatillo.

Green salsa is an essential ingredient in sopes; thus, have I been assimilated.

"If Porfirio Díaz would have been allowed to do what he wanted to do, then Mexico might be even more powerful that the United States of America is now," Juan told me.

"How so?" I asked.

"The oil. He could have controlled the oil and then Mexico would have been in a position to dominate instead of be dominated. Díaz wanted to industrialize Mexico, to make it compete with the United States. I wrote a paper on it in high school," he answered.

"Mexican oil really didn’t become an issue until around nineteen hundred and twenty, and it wasn’t even discovered in Mexico until ten years before that. And Díaz sympathized with the rancheros, he even encouraged their encroachment onto publicly held land wherever possible. The rancheros didn’t want modernization, it would have hurt them financially, so basically Díaz killed his own attempt at modernizing Mexico," I said.

Juan, and the friend he was with, both stopped and stared at me for a moment.

"Hey, I live here," I told them. "The least I can do is to learn a little bit about your history."

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori, after eliminating his political opponents either through murder, monetary manipulation, or plain old intimidation, led Mexico into its last revolution. Initially he gained office through the widespread civil unrest where people began to demand a one-term limit on the presidency, which he championed, and ran his predecessor out of office. His handpicked successor proceeded to screw things up so badly, that Mexico conveniently forgot all about the one-term rule, and Porfirio Díaz was again elected after somehow the constitution was changed to allow two terms in office.

Díaz then made sure that term limits were abolished altogether.

Eventually, as with all good dictatorships, it had to come to an end. After promising a free election, Díaz rigged the results for the last time. Francisco Madero had become increasingly popular, and his supposed defeat, along with too many other things to mention in one paragraph, started the ball rolling on Mexico’s second revolution. Díaz was eventually forced to flee and took exile in France. I find this ironic - even though Napoleon was long dead - as the French army during their occupation had captured and imprisoned Díaz, twice. Coincidentally, Porfirio Díaz is buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse, near Paris. So is Frédéric Bartholdi, sculptor of the statue of liberty.

Small world.

Both gave wonderful gifts to the United States of America, although Porfirio Díaz certainly didn’t mean to. The Mexican revolution, after its resolve in nineteen hundred and seventeen, led to years of instability and unrest and open intervention by the United States of America. It also led to the shortest term ever served by a president in world history, all of forty-five minutes, by Pedro José Domingo de la Calzada Manuel María Lascuráin Paredes. By the time Lascuráin’s name was pronounced, he had resigned. Some candles burn very quickly, I reckon.

Yet, Porfirio Díaz’s torch blazed brightly for over thirty years.

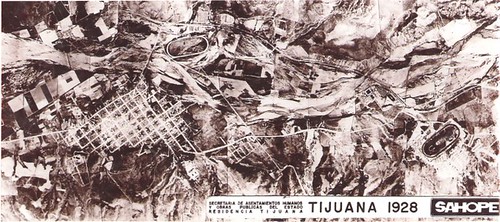

Porfirio Díaz is responsible for the existence of Baja California in its present geographical condition; in eighteen hundred and eighty-eight he decided that the federal territory needed to be divided into two districts, each of which were headed by chief executives assigned by the president of Mexico. Tijuana was still sparsely populated, but by the turn of the century, it became a place where people didn’t mind carving out a life for themselves. Tourists came along, and shortly after the Mexican revolution ended, the first racetrack opened in Tijuana, near the border.

This was in nineteen hundred and sixteen. Porfirio Díaz was dead by then.

The track was almost destroyed by a flood later in the same year, but the Casino Royal was demolished. They rebuilt that same track, but then built another one farther south, along with a larger casino and hotel complex (all part of the Agua Caliente complex), and Tijuana boomed. At least, until Cardenas closed the casino and racetracks opened in California, and the Hollywood crowd found entertainment elsewhere.

But history has been fixed now. This is my gift to Tijuana. Two race tracks existed simultaneously. I have proof, courtesy of my good friend Rene Peralta, and thanks to Daniel. Thanks, Rene and Daniel. And thanks, Tijuana, for everything.

1 Comments:

De Nada

I have posted a version of the picture with names and arrows, copy if you like

see you later, @ dandy i hope

r.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home