"Dictatorship naturally arises out of democracy, and the most aggravated form of tyranny and slavery out of the most extreme liberty."

- Plato

* * * *It certainly is not unreasonable to presume that almost everyone on the planet desires to help humanity to have everything nicer than it is. Some people look to achieve this through producing art, others through living their life as an example of what a good human being should be like, and still others by means of charity or generosity at appropriate times and in appropriate measures. In the United States of America, every four years the majority of people satisfy this longing to make the world a better place by voting for the president of their country.

People really believe that by voting for their candidate, then the world will somehow change for the better; and for this reason, I think that humanity fails because it is probably destined to fail.

Slightly more than one percent of the entire population of the United States of America is currently incarcerated in some way, for some offense committed against its society. This statistic means that slightly more than one in every one hundred people are defective in some way, that their sensibilities stopped functioning at some point and they abused the liberties granted them by their society. These defective people were then turned over to a prison for rehabilitation, a process whereby other people who are equally defective can help them in some way to become not defective and, eventually, regain their sensibilities and return to enjoy the liberties that their society grants them.

Obviously, this almost always fails to work, but society still seems to want to believe that its current practice of incarcerating criminals is the best alternative available.

Concurrently, thousands of people board airliners every day and the sky is filled with large jets that carry people all over the place, and these planes mostly take off and land without incident. Failure of a passenger jet to take off and land properly is rare, and accidents are scrutinized regularly to keep defective flights within acceptable limits. Currently, only one in eleven million passengers will die in such circumstances of failed aviation, and people seem to be generally pleased with this statistic. Apparently, society is much better at defying the laws of gravity than at fixing its own defective units. It would be unheard of to allow one percent of people that fly to be involved in a defective aeronautical incident, but it seems perfectly acceptable that over one percent of society is in jail.

The illogic of this paradox suggests that perhaps a lot more than just one percent of society is defective in some way. And this is just one paradox and one

type of paradox, and I am only considering the United States of America in this one example of this one type of paradox concerning paradoxes relating to humanity all over the world. But this one paradox reminds me that I am not here to present solutions, I am only here to try and see everything as clearly as I can and to report on it at infrequent intervals, in case someone wishes to understand what the problem really is. I can’t present solutions because I am not qualified to do so.

The Doomsday Argument supposes that all currently living human beings, given that they are existing in a random place in the linear timeline of the history and future of humanity, are in all probability near the center of the duration of humanity’s existence. Therefore, statistically, it can be assumed that the end of humanity can be calculated in some form, in order to predict the future. The Doomsday Argument does not take hardly anything else into account. It does not take into consideration such factors as nuclear weapons, the depletion of natural resources, economic collapse, mass starvation, genocide, or plague. The fact that the argument begins with the empirical observation concerning living human beings and ignores empirical evidence that would doom humanity regardless makes the Doomsday Argument a paradox.

Perhaps it should be called the Doomsday Paradox.

* * * *I walked back from the market the other day - I had just entered the narrow alley fit only for one-way traffic, a skinny sidewalk on one side and a broader path that I took on the other side. In one hand I carried a bag full of almost five liters of bottled Tecate, in the other hand I toted eight dollars worth of ingredients for chicken cacciatore, and the sun was hot and the breeze felt good. Traffic was light, it was just before rush hour, otherwise I wouldn’t have heard the voice from behind me.

"Dad!"

It was Anna, she had just passed by the alley in the taxi and noticed me from behind, then had the driver quickly stop, and was now chasing me as I turned and waited. She held out a hand as she approached, offering to take some of the burden off of me. Five liters of bottled beer gets heavy, even more so over the course of a couple of blocks.

"No, I’d rather carry all of it, both sides weigh about the same, so it’s easier to walk if my right and left sides are balanced," I told her.

She shrugged and then we walked together, the full-blooded gringo and the half-bred gringa, down the alley and cutting in through the pedestrian corridor that leads to the cul d’ sac and then to our front door, all the while explaining what chicken cacciatore is. Anna enjoyed the chicken Tetrazzini last week, so I figured that the cacciatore would be a nice balance, the tangy red sauce versus the cheesy white sauce. She often stops into the kitchen while I cook, watching mostly, asking questions sometimes, but enjoying her sense of smell whenever I lift pot lids for her.

"Balance," I told her when she asked about the chicken cacciatore.

Anna looked at me, awaiting an explanation.

"White cheese sauce, red tangy sauce," I told her.

I was thinking politically, too. Like, some sort of a balance of power, the Republicans and the Democrats, the

Pristas and the

Panistas, how you really couldn’t appreciate or understand one without the other. Anna didn’t much care at that point, she got busy downloading music into her ipod. Then, Dr. House came on television and we suddenly had something in common. We both wanted the patient to have lupus, but again, it never quite works out like we think it will.

Except that the chicken cacciatore was outstanding.

* * * *Monday, I left later than I wanted to leave, and I hadn’t crossed the border into the United States in many months, I was reminded of how much I hate it almost immediately. In the taxi

collectivo, the driver had the radio on loud and we all heard about the prison riots that happened the day before. People were calling in and giving their testimony, many civilians were apparently trapped in the madness. Mexican prisons are very unlike those in the United States of America.

Ironically, the taxi passed right by the penitentiary during all of the radio banter, and nothing seemed out of the norm.

Mexican prisons are like little cities, sometimes the family of the convict lives inside of the prison. If the convict’s family has money, then the convict can buy privileges, even a firearm. This seems surreal in comparison to other countries, but in Mexico it is something that everyone is aware of. No one seems happy about it, but since it doesn’t interfere with anyone’s life on the outside, it is something that is considered to be distastefully acceptable. Like prostitution, while it isn’t legal here, no one seems to care enough to try and eliminate it.

By the time I made it up to San Diego it was past noon, and I found Scott at our rendezvous point, reading the Los Angeles Times. We caught up, it had been a few months. He was wobbly from a bad encounter with some canned tomatoes that he had attempted to cook up in a rice cooker the night before, but he was recovering nicely. We spent some time inside of a nice Borders bookstore, and then walked the streets of downtown San Diego, we paused and I lit a cigarette. We chatted.

"Hey, Saints!" said a man dressed in a Steelers jersey, toting a backpack.

"I’m from New Orleans," he slurred in perfect Cajun, pointing at my hat.

"Really? What part?" asked Scott, smirking with amusement, politely engaging him for no apparent reason.

The drunk guy reached into his backpack while reminiscing with Scott about the

Big Easy, and he unscrewed a new bottle of conspicuous looking wine and staggered noticeably.

"I asked my sister for a hundred dollars and she sent me two hundred. Fuck yeah. I’m waiting for my girlfriend so I can take her to the movies or something," he told us before pulling the first long drink from his bottle.

I made an excuse and we left him behind, drinking his bottle of wine on the sidewalk outside of the bookstore. Scott and me went west for no particular reason, and reached a corner and waited to cross the street. Then Greenpeace greeted us; I was assuming that they wanted money.

"Hi, we’re with Greenpeace! We would like to talk to you about the environment."

We could tell from their shirts.

"Well, we need to cross the street," Scott told them.

"We’ll follow you," one of them said, and they did.

I must have made a good target for activists with my now-long hair in a ponytail and a few days of stubble on my face. They were nice, although I consider anyone wanting my attention on the city streets to be no different than someone who wants me to join their church, or their political party. They had no clipboards, no pamphlets, and no obvious propaganda to offer, except for the logo on their shirts. They attempted to engage me.

"I’m sorry, I don’t live in your country," I told them.

This works the majority of the time. It didn’t work this time. I should have just started speaking Spanish, instead.

"Where do you live?"

"Mexico."

"Oh, that’s great, we’re trying to do a lot of work down there…"

I held up a hand and chuckled.

"Good luck with that, they have their own idea about conservation," I said.

"Right, and that’s why we need people like you down there…"

We wished them a good afternoon and went about our business, catching up on what we had read and what we had written. We talked about how sick we both were listening to the banter about the upcoming presidential election. We eventually got into the trolley and talked about anything all of the way back to Mexico, where after we crossed the plaza on the south side of the pedestrian over the Tijuana River, he went his way and I went mine. I grabbed a cab and thought about how it was the first time over three months that I had seen another gringo other than my own reflection.

Scott is very liberal, to the point where, for a while, we couldn’t even talk about politics for a minute before he would go into a tirade about how George W. Bush should be tried for treason. I told him that he was ridiculous, that all presidents are simply puppets of the money that put them into office, that he was, in essence, wanting the head of the dummy and allowing the ventriloquist to remain free to simply find another dummy. We would always abruptly stop talking about it in those days, Scott was hell bent on his opinions.

Yet, Monday afternoon in San Diego, we could talk about politics coherently and rationally. I wondered if he had mellowed his radical mouth-foaming ranting because he had actually listened to anything that I had to say, but probably not. Scott has reached a milestone, in all likelihood. Sometimes it takes a good amount of time living out from the trees in order to see the forest for what it is.

Maybe Scott is seeing the true political machine of the United States of America for the first time.

* * * *The region of Chiapas has always been a base for rebellion, from the pre-Columbian era through the Conquest of Spain, into the assimilation period during Mexico’s civil war and subsequent revolution, and even now the indigenous Mayan tribes are not happy with the treatment they continue to receive. Chiapas is the poorest state in Mexico, but the richest in oil and natural resources. Yet, some of their indigenous people toil in maquiladoras for three dollars a day, working six days per week, barely making enough money to survive.

Fueled by ex-president Vicente Fox’s

Plan Puebla-Panama, a proposition that the region from Mexico’s State of Puebla all the way down to the country of Panama should become a corridor for improvements in infrastructure and manufacturing, factories are suddenly appearing. The plan is explained as providing an economic boost to the regions, as a way to attract private investors and create jobs and wealth in low-income areas of Middle America. This all sounds wonderfully capitalistic, like an economic utopia of sorts, and that it is in the best interest of everyone; but it isn’t.

It is a last ditch effort to compete with the Chinese.

Soon, the indigenous work force will stop showing up, their rock-bottom wages and the inability to change their pay and conditions will cause them to retreat. Some will return to the jungles and forests and a small percentage will eventually wind their way here, where the wages are slightly more generous. But those factories down there will eventually flounder and the railroads will become unused, and China will continue to pound out Nike shoes for two dollars a pair and then sell them for two hundred, until the Chinese workers decide that they, too, have had enough.

The solution to rebellion does not include political will, religious conversion, or the creation of an enclave economy.

In and near San Cristóbal, Chiapas, the Tzotzil Maya in eighteen hundred and sixty-seven had had enough, too. What was left from the elite Spanish after the Mexican civil war was still factional in the same way that they were when Spain had ruled Mexico. There were elite Liberals and elite Conservatives, and they ruled the region propped up by a still-powerful Catholic Church, their charge coming from support of the wealthy ranchers and land owners, and their society serviced by the indigenous people surrounding them. The elite Conservatives were in power at the time, and the elite Liberals bade their time waiting for the tables to turn. Both parties attempted to divide the indigenous support. The indigenous people were trapped in the middle, forced to attend Catholic churches and work at mostly conservative endeavors, and became restless and annoyed.

Near the indigenous village of Tzajalhemel, a Chamula woman discovered some magical

talking stones, and the old mystical ways of the Maya were again realized by several of the surrounding communities, and soon, Tzajalhemel became the religious center for the indigenous community. The elite Liberals, wanting to wrest power from promoting the lack of indigenous support from the elite Conservatives, went out of their way to encourage the Tzotzil and other tribes to withdraw their support from the elite Conservatives. Tzajalhemel then became autonomic in the minds of the indigenous, they established markets and schools and a monetary system based on a complicated yet highly effective method of barter.

The elite Liberals soon realized that they had underestimated the negative effects that the new cult was having on San Cristóbal; the churches were empty and local markets were almost vacant. This forced the hand of the elite Conservatives, who repressed the cult, seized the church, school, and market, in Tzajalhemel and then arrested the natives. The lack of a stable economy prompted new taxes to be imposed. Obviously, the natives retreated once again, and their society in Tzajalhemel was gutted permanently. After some of the natives decided to strike back, the elite on both sides slaughtered hundreds of Mayans, and this insurrection goes on and on.

Here we are in two thousand and eight, and even though the story changes from time to time, the tune remains the same.

And Greenpeace is preoccupied with saving whales while politicians are preoccupied with elections, while the media is preoccupied in informing society what elite money wants them to hear. Meanwhile, people suffer because of a struggle for power that will only culminate with the very few with money enough to control the outcome of the struggle ensuring that their money will buy the eventual winner of the struggle.

This happens in the United States of America as well - another seemingly irrelevant factor to throw into the Doomsday Paradox.

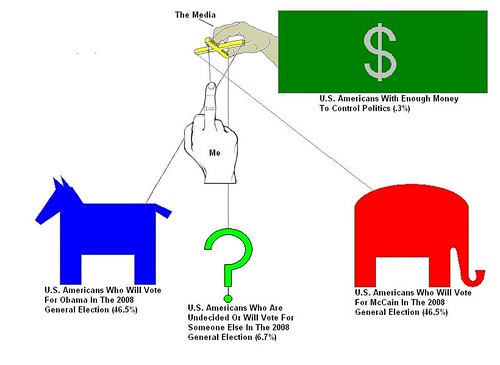

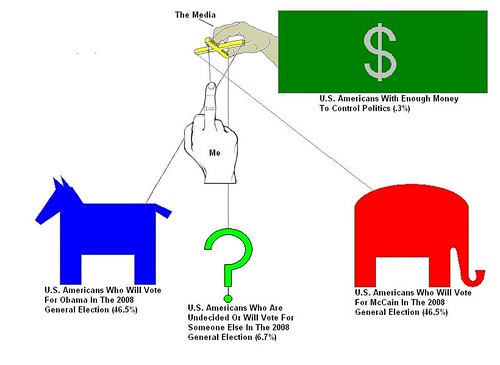

* * * *The problem with electing a president of any country is that the president isn’t really the elected party, it is the money that is behind that person that is actually elected. Less than one-third of one percent of the population of registered voters in the United States of America constitute the money that backs both primary candidates, and in order to protect their holdings, they often hedge their bets on both candidates. This ensures that their holdings, in the form of corporations and investments both in the United States of America and abroad are secure and protected by the government in power. Below is a diagram to help and explain how this works and where I see myself in the scheme of its system:

(How the election process in the United States of America really works and my role in all of it.)

The media is the key to assuring that people are distracted enough from the real process in order not to see it. The ideological differences in the platforms of the political parties are exploited, keeping potential voters embroiled in argument that is actually irrelevant. The truth is that liberal politicians will be conservative and conservative politicians will be liberal in order to gain election or re-election. This morning, the conservative president of the United States of America announced that the treasury would magically make a half-trillion dollars appear in order to infuse a collapsing economy with new life. Economically, this is the most liberal act that has been performed by an administration since Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Does anyone really think that politicians decided this? Or perhaps, was it the money that elected the politicians?

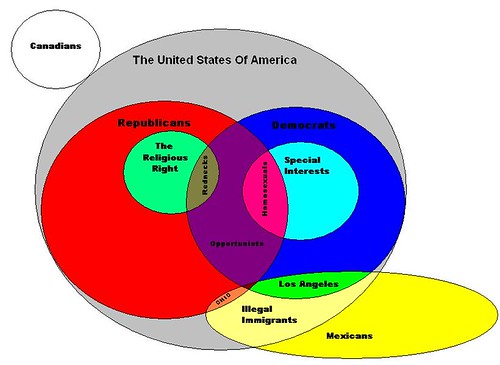

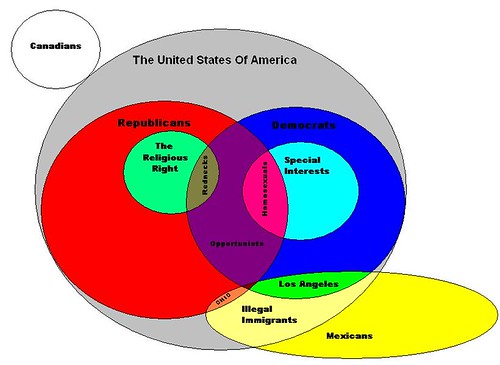

People would rather believe the media is simply reporting the truth. These same people see themselves precisely where the media has placed them, pigeonholed and seemingly enjoying it. Perhaps it is satisfying some crisis of identity within society, maybe people just want to know how they are fitting in. Below is a diagram that shows how the media perceives the voting public in the United States of America:

(How the media in the United States of America views the voting public.)

None of this provides anyone with any answers, and since I lean toward empirical evidence that humanity exists only to destroy the planet that it lives on, then many of these observations are nothing more than irrelevant musings. I am delighted to point it out, regardless, should anyone wish to consider that there might be a solution. Maybe anthropologists will discover a way to fix everything, maybe the answers lie in the past, with the Maya. The Mayan calendar ends in four years, is it possible that they discovered their own version of the Doomsday Argument? When the Tzotzil retreated to Tzajalhemel in order to re-form their civilization all over again, maybe they were onto something that could have provided some missing clues.

Perhaps certain astrophysicists and philosophers should stick all of this into their Doomsday Paradox, maybe the answer lies there.