I met up with Scott accidentally when I got back to Centro after a short trip into the United States of America, I saw him on the street, crossing Avenida Revolución. It was almost ten in the morning, so we went over to the Nuevo Perico and opened the bar. The sun was warming the sidewalks slowly, and we sat there for a while and drank Dos Equis Ambar from the tap and caught up on everything I miss because I don’t get out of the house much these days.

"I’ve just been writing and cooking," I told him.

"Oh, did you hear that Stanley died?" Scott asked.

"Yeah, a few weeks ago I was at the Dandy del Sur and Aida told me. It was funny because she was so sure that I would somehow be rocked by the news. I just had to tell her that I didn’t get along with Stanley all that much, but I was sorry that he died. She seemed surprised, like all of us gringos love each other’s whiteness or something," I said.

Stanley was one of the most negative and depressing individuals that I ever knew. Almost bald, with a long and very out of control white beard, the first thing that Stanley would tell you, initiating a conversation, was that he wanted to kill his ex-wife. Then, he would tell you about how his paintings were worth thousands of dollars but that he couldn’t sell them in the United States of America for this reason or that reason, and that his artistic ability is recognized in France and Spain. He would go on about how he wanted to go to France and Spain but couldn’t, which would bring the one-sided conversation back full circle about him wanting to kill his ex-wife.

Stanley and me had this same conversation on three separate occasions, many years ago. The last time that he initiated verbal communication with me, I wanted to pull my eyeballs out of the sockets and stick them in my ears, and then it got to the point where I had enough. It was as if Stanley enjoyed swimming in his misery. But that wasn’t enough for him, he wanted to bring everyone else into that putrid pond water that held his soul, as if everyone else should want to feed off of his negativity and loathing.

"Stanley, you are the most miserable human being on this planet!" I finally told him, and walked away.

We never spoke after that. He was around occasionally, but we successfully ignored each other. Scott got along with him well, that while acknowledging Stanley’s preference for suffering and grieving as a life experience, they were both artists and drew and painted. Stanley lived in Playas de Tijuana, which is a large section on the beach a few miles west of Centro. He was in his sixties.

Miserable no more!

Jody came into the Perico at noon so we sat and drank and talked for a while, I bought both of them beers, I really miss seeing them as often as I used to. Another gringo came in, a guy that has been around for a few years, another guy that I don’t much care for. The first time that we met, he bummed a cigarette, and while I normally do not hand out cancer I gave him one anyway. Twenty minutes later, when I refused to give him another, he became irate. I told him to purchase his own cigarettes. We never spoke after that.

He chatted up Jody mostly, apparently he has learned how to buy his own cigarettes, until Jody left and then Scott turned to me.

"Dave, come with me up to Zona Norte, I’ll show you my pad."

The other guy, the gringo that didn’t leave with Jody, made overtures about wanting to tag along. Scott, ever aware of my wariness of many of the part time gringos who show up out of the blue and vanish just as quickly, blew him off. We finished up our beer and got out of there, heading up toward Zona Norte.

* * * *I always found it amusing to look at my birth certificate, in that I was born in San Diego and yet never really knew the city until after I moved to Mexico and then eventually worked in San Diego for many years in various locations. Working over there taught me San Diego, or at least most of it, in more ways than one. I pull out a copy of that birth certificate now, every time that I cross the border. I present it along with my California State identification card.

I used to have a passport, but it expired long ago.

When I present the birth certificate and the identification card, the Department of Homeland Security representative either looks at everything and I move on, or they punch in some information so a computer can determine anything that would make me a threat to enter their lovely country. Or else, they argue with me over not obtaining a passport. I argue back that I only need to mail a letter and cash a check, but apparently my length of stay only being forty minutes does not impress them. They let me enter regardless; at least, they have so far.

I was going to go back over Tuesday, but a funny thing happened when I woke up that morning: no water. No water means no shower, so I put off my journey until the water returned, which was last night. The water company doesn’t hand out notices down here, they simply turn the water off and perform whatever repairs or maintenance is required, and it is only through the gossip and sometimes the local news that anyone has any advance warning. Rocio’s mother had heard something, she filled about a dozen five-gallon buckets in her own home, and then early Tuesday morning while I was still sleeping she filled some large containers that we have here for just such a purpose. For a few of days, we used the downstairs bathroom for everything, and flushed the toilet by dumping a bucket of water into the commode in order to empty it.

Gravity is wonderful that way.

Rocio, Anna, and Sharon took sponge baths until the water pressure returned because they needed to leave every day, so I waited patiently since I am in no hurry. Meanwhile, I cooked food that requires little in the way of pots and pans, we ate hamburgers that I fried using an electric griddle and fish tacos that I cooked in a deep fryer. The hamburgers are very good clones of an

In-N-Out Double-Double, and the fish tacos are from the same recipe of Baja’s finest, right down to the beer-batter and the fresh tortillas. The dishes, what few were dirtied, were washed using our drinking water – an expensive but necessary use of what normally is only consumed in cooking and liquid refreshment applications.

I have often replied, when asked what living in Baja is like, that this is a campout in a cement tent.

Sometimes it really is.

Last night, the water returned, and I awoke this morning anticipating another border crossing and then, perhaps, meeting up with Scott and Jody afterward. I matched a cigarette and listened to the radio, thinking about getting some Cuban coffee on the way over. I am hooked on the dark, rich flavor, which is something that couldn’t happen in the United States of America since the apparent key to defeating communism precludes uniquely robust coffee and genuine Cohibas.

Then, the voice on the radio told everyone that the line to enter the United States of America was over three hours long, attributed to Mexican holiday celebrating the

Virgen de Guadalupe. Many people take this day off, attend mass, and then head over the border to do some shopping. No matter how long I live here, at least some of these holidays will always elude my peripheral vision. There is a station on this Mexican cable that we subscribe to, and it covers nothing but the lines at the three border crossings between Tecate and the Pacific Ocean. The cameras, panning endlessly to give as many aspects of the border wait as necessary, confirmed what was said over the radio. The wait to cross was ridiculous. I will go Monday or Tuesday then, and imagine that today Scott and Jody are enjoying the

Coahuila, much like we did the last time I was given the tour of the new and improved Zona Norte by Scott.

Besides, I don’t need to go back there anytime soon.

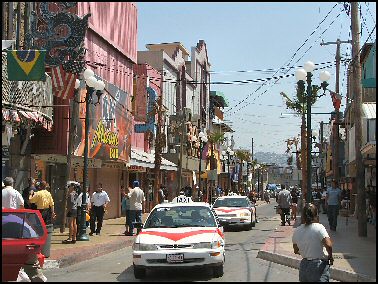

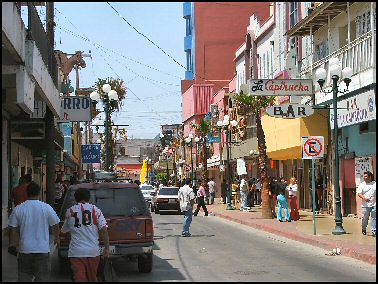

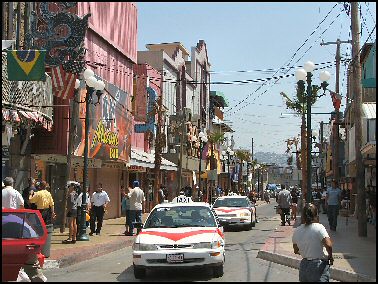

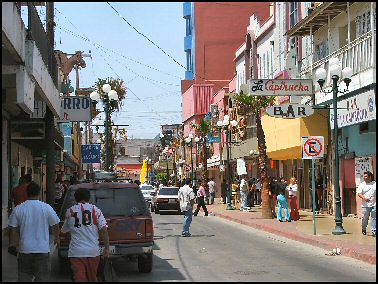

* * * *Scott led, and I followed him up to the

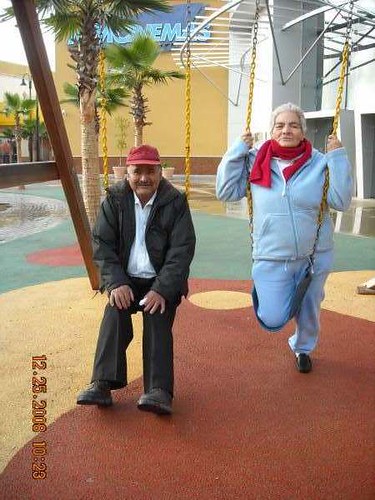

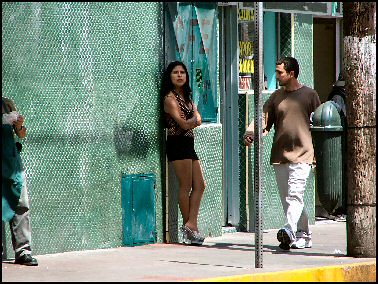

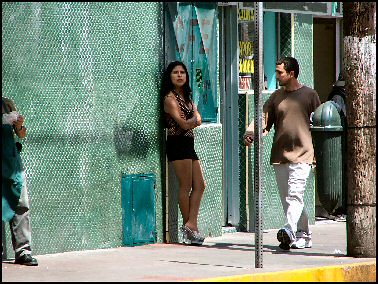

Coahuila, he is one of a few people who actually walks faster than I do when left to his own devices. The streets are the same as when I last walked them, except cleaner and rebuilt. There are even palm trees now. The prostitutes are still there, except that there are more of them, a lot more, and they appear younger now. I am older. It seems relative somehow.

The economic crisis and lack of tourism probably has something to do with it as well.

We ran through perhaps a half-dozen bars, most of them decorated with young dancing girls. The two most impressive locations were

Adelita, a mainstay in Zona Norte, perhaps even a landmark, filled with girls of every flavor. They have remodeled since I was last there over ten years ago, they are always remodeling here. But the menu remains the same. The other bar, which I can’t remember ever having entered, is

Hong Kong, which baffled me. Scott took me through everything way too fast before we finally went up to his apartment next to the Chicago Club.

Scott’s apartment is a glorified hotel room, a single room with a bed and an attached bathroom and no room for anything else. There are paintings and drawings scattered everywhere, except for one side of the room which is piled three feet high with old newspapers and magazines, like a long line of sandbags might fortify a bunker. There was no alternative to some clutter because of the size of the room.

"They keep bitching at me to throw these out," Scott laughed, looking at the stacks of print.

"Come on, I’ll buy you a beer, I want to go back to that Hong Kong club and take some mental notes," I told him.

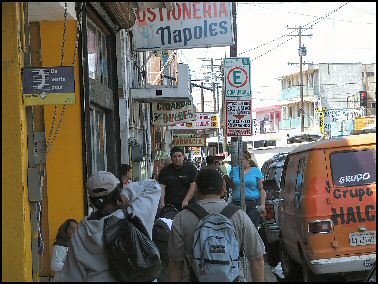

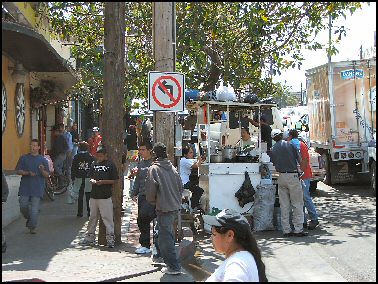

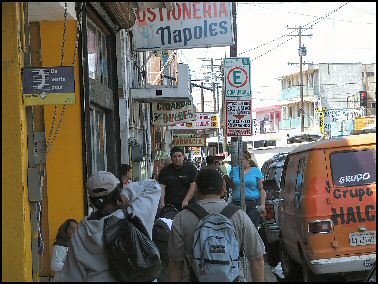

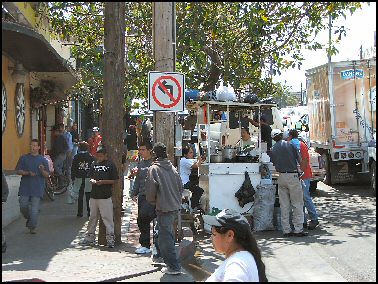

We left, into the streets, onto the narrow sidewalks navigating through crowds, past taco carts, watched suspiciously by the same people that remained throughout the remodeling of the red light district. They painted lipstick on a pig, and while the pig looks a lot nicer, it still smells like a pig. It’s nice to know that the Coahuila hasn’t lost any of the charm.

The first time we saw Club Hong Kong, Scott led me in through one entrance and out through another, there was barely time enough to soak it all in. This time we sat, and I bought us some beers. It is spacious; spanning the length of a very short city block, you can enter through either door on two parallel streets, and unlike most clubs in Zona Norte, this place was relatively clean and well decorated. I counted six customers other than Scott and me, and I gave up on counting how many girls were in there.

Maybe fifty girls were in there, dancing in various locations, including on top of the bar.

"Check that out, Scott, they’re being directed where to go," I said.

There was an older woman, perhaps forty, with a wireless headset, directing the girls where to go, rotating them like a choreographer. Upstairs, against railing, some girls either danced or just stood. Scattered throughout downstairs, there were several small platforms, which held two or three girls dancing in various states of undress, and everywhere else they either posed or moved playfully to the music. Next to our table, they rotated two girls upon the small platform, and I looked up. One girl danced topless while the other danced in a short skirt and a flimsy top, and wore nothing else except for high heels. She made sure that we got a nice view looking up at her, and might have been disappointed in my lack of interest.

I have seen plenty of strippers, but fifty girls for eight customers made the scene completely surreal.

"You should see this place at night," Scott told me.

We finished our beers and left, there wasn’t a girl in there under the age of twenty-five.

"Anything else that you want to see?"

"Not especially," I answered.

"Well, then I want to take you to this bar that Jody drinks at sometimes. It’s a dive, but it’s full of locals," Scott said.

After a short walk, we parted the thick, vinyl-coated curtains at the door, past the disinterested doorman, into a small place with about twenty people inside. There was just enough room at the bar. The jukebox blared Norteño music while a couple of people danced, a working girl and a patron, and then another girl dressed in sweats went up on the stage and gyrated ridiculously, which chased the couple back to their table.

People looked on, bleary-eyed and stone-faced.

"She’s pregnant," I said.

"Before she got strung out on drugs, she used to work here," Scott informed me.

I stopped watching her. Jody walked in, and we all chatted about whatever, but I mostly just listened and realized that no matter what they do, it won’t change Zona Norte. I thought about Stanley, and how nothing would have changed him either, that some things and some people aren’t meant for change. New sidewalks and palm trees can’t transplant new people. There will always be fifteen-year-old prostitutes and pregnant crack addicts there. And the gringo money, like when the water supply is cut off and other means are used to survive without it, will always find a way to trickle into that place and keep it going like it always has.

The five-gallon plastic buckets replace the free-flowing water pipes.

Me and Scott eventually wandered back up to the Perico and had a few more beers up there, where the girls aren’t so young and the money isn’t nearly as precious.

(All images courtesy of Eric Rench)